OrchestraOne Score Club - Special Edition

Hello everyone and thank you for taking this special journey with us. We will spend the next four weeks exploring the rich history of Black and African Diaspora music in the United States, chronologically. Each week will be a new era,and a link will be posted to all of our social media accounts and sent out in our email blast. We are all so excited to dive into this music, so let’s get started!

Week One

Pre-Civil War music by peoples of the African Diaspora.

Roughly 14 million Africans were taken from their homes and shipped to the New World to be enslaved. From 1626 to 1875, just over 300,000 landed in what we now call the United States of America (for an in-depth look at slave trades from all over the world, visit www.slavevoyages.org). While they were forced to leave their material possessions behind, they carried with them their culture, spirit and life-view. From within them, came beautiful works of music, art, and literature.

Music on the Plantation

Like most folk music from around the world, music being performed by enslaved peoples in the south were used for specific purposes and events. Stemming from the music that these slaves knew and performed in Africa, (The banjo, for example is the result of a traditional African instrument made from a hollowed-out gourd) this music was passed down almost entirely orally, with subtle, or very large changes made along the way. All of this music was used as a way to find hope, solace, and build community.

“The Old Plantation (Slaves Dancing on a South Carolina Plantation)” [ca. 1785-1795]. Attributed to John Rose, Beaufort County, SC. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, VA

One of the most well-known forms of music from these communities were Slave/Folk Spirituals. These spirituals were sung in the plantation fields, were often improvised and sung in a call and response form, where one leader would sing, and the rest of the group responded in kind. While the content of these Spirituals were typically religious in nature, these slaves found their own interpretation of the Christian texts; one that they could more closely identify with as Africans. Frequently, they would diverge from their white-Christian counterparts in style as well, being more upbeat in nature.

This video is a great example of the call and response tradition in these Spirituals. Already you can hear the beginning of new musical genres like the blues and jazz. By Ed Lewis, as recorded by Alan Lomax. From Sounds of the South

The Plantation Singers performing, “Swing low, Sweet Chariot”

One of the best known spirituals that came out of this tradition was is famous '“Swing low, Sweet Chariot.”

I looked over Jordan, and what did I see,

Coming for to carry me home;

A band of angels coming after me,

Coming for to carry me home.

If you get there before I do,

Coming for to carry me home;

Tell all my friends I'm coming too,

Coming for to carry me home.

Chorus

Swing Low, sweet chariot,

Coming for to carry me home,

Swing low, sweet chariot,

Coming for to carry me home.

These kinds of spirituals, along with more secular slave songs, were collected in the field by northern abolitionists like William Francis Allen, Lucy McKim Garrison, and Charles Pickard Ware. These three compiled a book of 136 of these songs titled “Slave Songs of the United States.” The Smithsonian has this book online and for free, here.

For a more detailed look into the music of enslaved Africans on plantations, “The Sounds of Slavery” by Graham and Shane White is a great resource and can be read here.

Music Off the Plantation

Off the plantations, music continued to hold an extremely important role in slave communities. Many slave “musicianers” are thought of as the founders of true American Folk music and gained an elite status within their communities.

This status came from two places. First, their skill and talent afforded them some special privileges that their fellow non-musician slaves did not have. The slave owners, in need of entertainment, would allow these musicianers to travel to different homes and mingle with other whites. Some were even able to earn an income and were frequently able to avoid the constant white supervision. The status given to these musicianers from their slave owners was important in giving them elite status among their community, but it’s what these musicianers did for their own community that was so important in solidifying their roles as central figures in their community.

Like the folk music in Eastern Europe, South America, among indigenous Americans and all over the world, much of the music enslaved African musicians were performing was for dancing. On a weekly basis, usually on Saturdays, enslaved communities would congregate for “Frolics.” These Frolics were remarkably important not just for the evolution of their own genre of music, but in strengthening the ties within communities, providing a place for socializing and joy, and solidifying the important role for musicianers.

The music performed at these frolics were almost always accompanied by dance, and many different styles of music came from them including Ballads, Jigs, Reels, and, as shown in the video here, Ring Shouts. These styles of music that evolved quickly from traditional African roots combined with the new tradition of Spirituals, were an important step in the evolution of the Blues, Gospel, Jazz and later, contemporary popular music. Compare some of the videos shown here and the line from spirituals to the blues especially is evident.

This video in particular shows how these communities seamlessly combined their own African traditions and their new Christian beliefs (upon conversion from their masters) and also points into the future in many ways. The clapping echoes the drumming tradition from Africa, the lyrics come from the gospel, and the style in which they are singing (the semi-improvised call-and-response, rhythm and harmonic language in particular) point forward to the soon to be invented blues.

There are many first-hand accounts of how these frolics helped to build community, including this quote from Mary Gaffney, an ex-slave: “I will never forget those old dances out there in the woods…these dances lasted all night long as they was no one to bother us and the next day was a holiday.” The holiday Mary speaks of is church Sunday, where yet another evolution of African American music began to evolve.

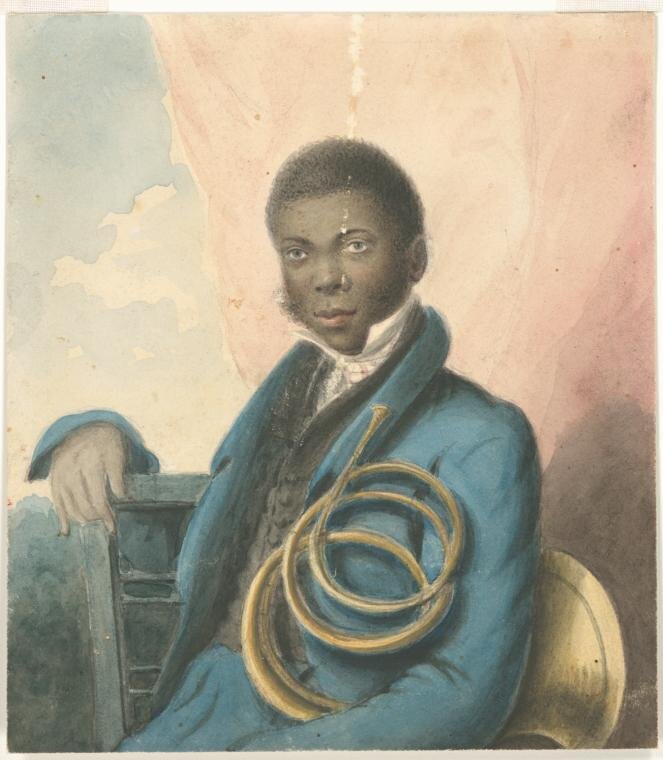

Professional African American musicians during this period were rare, even in the north. However there were some who were able to create successful careers. Chief among them was Francis Johnson (June 16, 1792 – April 6, 1844), a virtuoso bugle player and violinist as well as prolific composer. He was the first African American to publish music, tour Europe and perform in integrated concerts. His compositions, which included ballads, operatic airs, band and orchestra pieces were highly regarded, and many believe that European composers including Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel were influenced by his unique style.

Francis Johnson (June 16, 1792 – April 6, 1844)

Unfortunately, no complete sheet music survives today, partly because of systemic racism, but also because he very rarely wrote full scores and parts. He was so prolific and in demand that time constraints forced him to write in short-hand and tell his bands (like his all-African American band in Massachusetts) what he wanted right before the performance. This is one of his marches that was reconstructed from his notes. While not exemplary of his style, it is one of the few recordings that can be found.

Even though Johnson’s music is almost entirely lost, his impact in the United States cannot be overstated. Songs of his titled “The Grave of the Slave” and his “Recognition March on the Independence of Haiti” were extremely important in convincing northern whites to join the Abolitionists. He is the founder of the classical “pops” concert, and even played for the Queen at Buckingham Palace. He also taught and inspired an entire generation of African American musicians, including Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins, who we will talk about next week. The University of Pennsylvania has an informative article about Johnson in their archives, here.

Art and Literature

While our focus for the next four weeks is on music, we would be remiss if we did not discuss, to a small degree, the accomplishments of African American artists and writers before the civil war.

Artists who were enslaved gained similar privileges to their musician counterparts. They were frequently hired out by their slave owners and were sometimes allowed to keep some of their earnings. In a few cases, this allowed some slaves to buy their freedom. Some of these artists were goldsmiths, instrument makers, carpenters, etc. One genre that thrived and still today holds a place in the artistic history of the United States is Southern quilt making. Harriet Powers (1837–1910) was born into slavery and today her quilts are known as masterpieces of folk art. Few survive today and none from before the Civil War, but this is one of her later quilts.

Harriet Powers, Bible Quilt - 1898

Another African American founder of Folk Art in the United States is John Bush, who lived in the first half of the 18th Century (exactly dates are unknown). He was a soldier in the Massachusetts Militia and had a niche specialty of carving powder horns. One of these horns is seen here. This particular one is still traveling in art shows around the world and has been continually used as an example of superb craftsmanship.

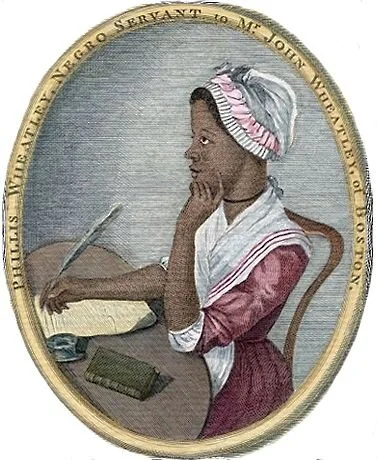

There were African American painters as well, who all contributed to the American style of classic painting, especially portraiture. Two of these painters included Joshua Johnson (c.1763 – c.1824), and Scipio Moorhead (active c. 1773). Both were enslaved and later gained their freedom. Typically, these painters and others painted portraits of their slave owner families and close relatives/friends.

The Westwood Children, ca. 1807. In the collection of the National Gallery of Art

Phillis Wheatley, possibly based on a portrait by Scipio Moorhead, in the frontispiece to her book Poems on Various Subjects.

The principal form of literature that came from enslaved Africans are Slave Narratives. They were first published in England in the 18th century by white abolitionists to bring attention to the reality and horror of enslaved life. Some of the most famous authors of these narratives are Harriet Tubman, Harriet Jacobs, and Frederick Douglass. These were first hand accounts from current slaves or slaves who had escaped or otherwise gained freedom.

The first of these to be a best seller was The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or, Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself (1789). The text of these narratives were always biographical. This is a scene that describes his experience on the ship that took him to the New World:

“…their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and, quite overpowered with horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. When I recovered a little I found some black people about me.…I asked them if we were not to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and loose hair.”

These Narratives remain some of the most influential early writings in the United States, and also stand as a remembrance of the atrocities of slavery. White abolitionists would also publish fictional accounts of slavery to show what horrors occurred on the southern plantations. The most famous of this is Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Title page from the first edition of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or, Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself (1789)

![“The Old Plantation (Slaves Dancing on a South Carolina Plantation)” [ca. 1785-1795]. Attributed to John Rose, Beaufort County, SC. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, VA](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d6abc1f9e0b8f0001614dc9/1591367056867-RYDT0NUYH89KJ7Z1LODM/slavery-header.jpg)